The Anniversary of the Great Adventure

It’s not the years, honey. It’s the mileage.

Indiana Jones

It’s hard to imagine a world without Indiana Jones.

Of course, I say this as someone who was all of two years old when RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK arrived in cinema, but there’s something about the character, the film, and the music that feels absolutely timeless. Perhaps it’s more that I don’t want to imagine a time before Indy and that ubiquitous theme that goes along with him. At the same time, it also feels incredible that we are celebrating the 40th 44th anniversary (the film was released June 12, 1981) of a movie that feels, in a lot of ways, as though it could have been made today1.

There are so few perfect movies out there, but I dare say this is one of them. There is nothing that doesn’t work for me; nothing that I would change. While I would love to visit the alternate universe where Tom Selleck played Indiana Jones, I don’t think I would want to live there. Because this is the role Harrison Ford was born to play. Combining his Han Solo persona with a bit of Humphrey Bogart (a dash of Fred C. Dobbs from THE TREASURE OF THE SIERRA MADRE and more than a sprinkle of Charlie Allnut from THE AFRICAN QUEEN), Ford has never been better than in this film. Consider that he portrays someone showing at least three exteriors: 1) the swashbuckling adventurer, 2) the professor, and 3) the world-weary individual behind both who is only able to come out when he lets his guard down.

Of course, a big part of the character of Indiana Jones comes from his now-famous theme. With the involvement of both Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, it seems obvious now that John Williams would provide the score to RAIDERS. Williams, who had already developed a mind-boggling number of famous themes, would once again produce an iconic motif for one of the most recognizable characters in cinema. And its creation is truly a case of Spielberg having his cake and eating it too, as Williams wrote two possible themes for Indy, and Spielberg’s reaction was to use them both (the first becoming the main theme and the second becoming the bridge).

One of my favorite things about how Williams uses the theme is that he actually withholds it for most of the opening sequence. Instead of a big, rousing rendition of the “Raiders March,” the film instead opens with the Paramount mountain dissolving to a mountain in the jungle of Peru (a brilliant choice by Spielberg) and a mysterious, winding melody played predominantly on bassoon2 (Excerpt 1).

Williams evens resists an obvious place to use the theme—when Indy has whipped the gun out of the hand of a would-be killer, and the frame fills with Harrison Ford’s face. Instead, we get blast of foreboding low brass and more mysterious music (Excerpt 2).

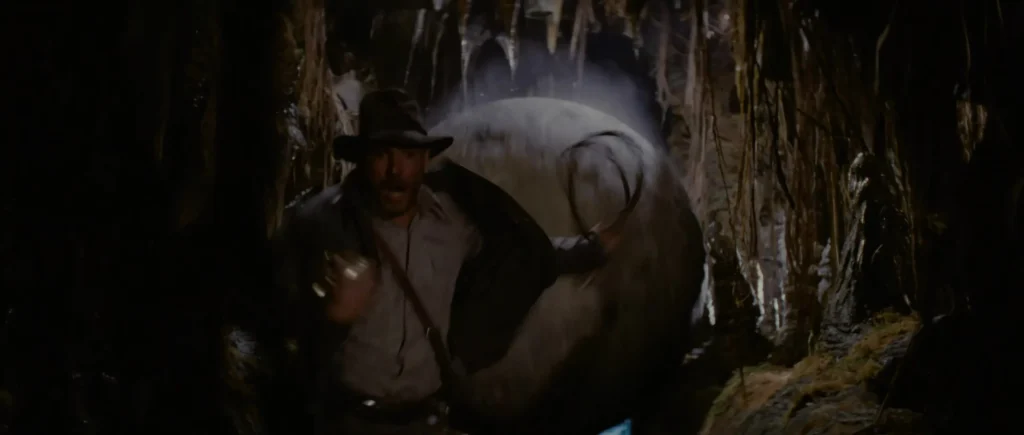

Of course, this makes sense when you consider that we don’t know who Indiana Jones is at this point. His mysterious nature both in the film and in the music continues as he and his assistant Satipo (Alfred Molina in his first major movie role) enter a temple in search of a golden idol. The two cues that follow are programmatic movie music at its finest. While I will admit to having seen this movie countless times, I can listen to these musical moments and see the movie in my head: Indy swinging over the chasm; approaching the dais containing the idol while avoiding the booby trap spots on the floor; replacing the idol with the sandbag; failing to jump the chasm to escape; and of course being chased through the tunnel by a giant boulder. It all works perfectly with the visuals, and these two cues and moments have been parodied many times, with good reason!

In all this excitement, we still haven’t heard the famous theme! It’s not until later, when Indy grabs a vine and swings into the lake to reach his waiting plane, do we hear the first bars of the “Raiders March,” which then rounds out the rest of his escape as we get both the A and B themes in succession.

Themes for Good and Evil

This is a John Williams score, so the Raiders March is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to thematic material. His theme for Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen) is a logical extension of the love theme Williams wrote the previous year for Han Solo and Leia Organa in THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK (1980). Similar in style, Marion’s theme draws on the romantic stylings of music written in the 1930s and highlights Williams’s skill at writing for woodwinds. My favorite rendition appears in the film as Indy and Marion are finally safe (so they think) from the Nazi’s and are finally able to relax. The score swells as it looks like the romantic tension that had been building throughout the movie is about to be released…only to have Indy fall asleep. It’s a wonderful moment told both visually and through the performance of the music.

An accompanying theme for Marion is one that Williams wrote for her medallion: the “Headpiece to the Staff of Ra” that serves as the film’s first MacGuffin. It’s evocative and slightly exotic, a feel that is helped by its often being played by double reeds.

The Headpiece is merely the first clue to obtaining the true object of the film: the Ark of the Covenant. The theme for the Ark is introduced early on as Indy explains to a couple of men from Washington, DC exactly what the Ark is, what it looks like, and what it is purported to do. It’s a theme that demonstrates Williams’s considerable talent as it portrays both beauty and danger at the same time.

In perhaps the best scene in the film (and certainly one of the most famous), Indy goes to the “map room” to use the medallion to determine where the Ark is. It is in this scene that the Ark of the Covenant theme is brought to the fore—or is it?

One of the brilliant things Williams does with the score (and there are many) is that he never lets the Ark theme resolve (fully play out) until the climax of the film. Before then, even in this scene of massive import, the theme leaves the listener hanging, as a melody that feels like it is going somewhere is constantly interrupted, instead returning to its opening moments. This is first achieved by cutting to other action outside of the map chamber, but even as the cue reaches near orgasmic levels with choir and orchestra as the sun moves into position, we never hear the theme in its entirety.

It is not until the Ark is opened at the end of the film that we hear the theme in full, as the power and wrath of God is unleashed upon Belloq and the Nazis. It is here that the full theme, initially beautiful in its presentation and incorporating the Medallion Theme as well, becomes twisted into something terrifying as the power of the Ark is unleashed, killing anyone who dares to look at its awesome spectacle. A full and complete statement of the Ark Theme rounds out the sequence as the inferno sweeps up everyone except for Indy and Marion.

The Return of the Great Adventure (Score)

Of course, for a film so firmly rooted in the 1930s style serials, RAIDERS would succeed or fail on the strength of its action sequences. And boy did the film deliver, boasting multiple sequences that any other film of the time would kill to have as its climax. And unsurprisingly, John Williams was up to the task as well. That said, the first big action set piece after the opening sequence in Peru—a superbly staged shoot-out in a Marion’s bar as it burns to the ground—went completely un-scored.

Williams’s next opportunity to score an action scene comes in the streets of Cairo, where Indy and Marion are pursued by Nazi agents. The scene and the score both play up the tongue-in-cheek aspect of Indy and his adventures, with Williams using a bouncing, winding woodwind theme throughout. When Marion confronts her knife-carrying adversary with a frying pan, a humorous descending motif plays (one that Williams would later reference in TEMPLE OF DOOM as part of a fan service in-joke).

And in what is undoubtably the funniest moment in the film, Indy comes face to face with a man wielding a massive sword. Williams provides an over-the-top flourish of music to accompany the equally flamboyant swordsmanship…until Indy remembers he is carrying a revolver.

Of course, the pièce de résistance for both action and score is the desert chase sequence, where Indy must hijack a moving truck carrying the stolen Ark of the Covenant. Kicking off with a driving rhythmic motif in the brass, Williams feathers in a light version of Indy’s theme as he declares that he is going after the truck, though perhaps not without a plan in mind. We are then treated to a full-on heroic version of Indy’s A-theme, which is contrasted with Williams’s motif for the Nazis, as they surround Indy in the truck (Excerpt 1).

“Meet me at Omar’s. Be ready for me. I’m going after that truck.”

“How?”

“I don’t know, I’m making this up as I go…”

The cue continues to build as Indy dispatches Nazis in motorcycles, Nazis in Jeeps, and Nazis climbing on the outside of the truck itself, until finally one manages to shoot Indy in the arm. It is at this point that one final Nazi is able to take advantage and commandeer the truck, throwing Indy through the windshield in the process. In one of the great real-life stunts ever put to film, Spielberg and his crew pay homage to the famous stagecoach sequences of old by having Indy go under the truck, eventually being dragged from behind by only his whip. Here, the score moves to a rousing version of Indy’s B-theme as he wills himself back onto the truck, eliminates the final Nazi, drives Belloq and company’s car off the road, and drives away, with a quiet but triumphant version of the A-theme to round out the cue (Excerpt 2).

To be honest, I should have simply linked to the entire cue here, but unfortunately the most recent release of the RAIDERS score absolutely butchers it with several cuts that are simply awful. If you can find it, the 1995 release from DCC Compact Classics contains the cue in full; however, it is missing other cues that only the later 2008/2009 releases have, so your mileage will vary in terms of which disc you may prefer.

Despite these occasional hiccups that are entirely the fault of the labels putting out the scores (thanks to the visuals, sound effects, etc., most of the bad edits that mar the listening experience go unnoticed when watching the film), RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK stands as another in a run of simply superb score/film combinations that John Williams was a part of in the late-70s/early-80s. And it’s hard to believe that as we celebrate its 40th anniversary this year, the franchise is still alive with a fifth installment expected soon. Until then, the original Return of the Great Adventure remains, and to quote Marcus Brody: nothing else has come close.

Related Posts